Carbon capture and storage (CCS) has been on the research and political agenda for some time now, but there has been a surge in media coverage recently in the European Union (EU). This is in part due to the announcement of the results of the CCS funding commercialisation competition run by the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) in the UK and also the second call for European Commission (EC) NER300 proposals which was announced on 3rd April. This, together with a peak in discussion in the EU on shale gas and climate change targets, has put CCS in the headlines again. General discussion on the development of CCS has been building for some time in conjunction with the controversial advent of shale gas in Europe. Carbon capture and storage is often touted as something of a catch-all solution to runaway carbon emissions – so why is CCS development moving so slowly?

What is CCS and what current research is taking place?

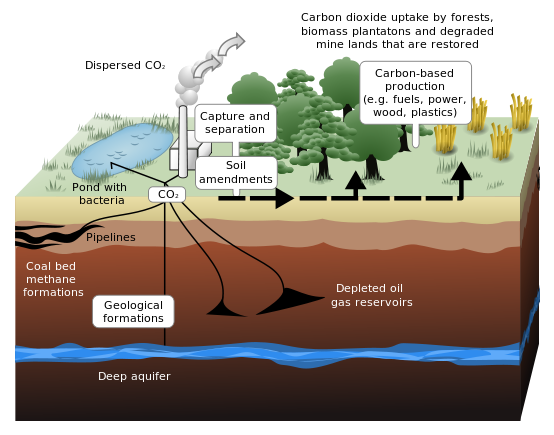

Firstly – how does CCS work? In terms of capture at a coal power station, there are three approaches: you can either remove the CO2 before the coal is combusted, scrub it from the exhaust gases after combustion or burn the fuel with extra oxygen so that the exhaust produced is almost CO2 free. But it is in the CO2 storage process that geoscience expertise is of particular significance, since geologic storage has huge potential for CO2 sequestration.

Schematic showing both terrestrial and geological sequestration of carbon dioxide emissions from a coal-fired plant (click for larger), (Source: Wikimedia Commons).

The majority of large-scale CO2 storage research in Europe has been carried out in the Sleipner oil and gas field off the coast of Norway (see map below), where, since 1996, a Norwegian oil company has been burying CO2 in the depleted reservoir. Here the CO2 is separated and then pumped into a saline aquifer in the Utsira formation – a 200-250 m thick massive sandstone. Sleipner was the world’s first commercial CO2 storage project and to date 8-9 million tons of CO2 has been successfully stored in the former oil and gas field, with a further capacity of up to 600 billion tons of CO2. Ongoing monitoring has shown that there has so far been no evidence of CO2 leakage which is promising for further development.

Location of Sleipner oil and gas field in the North Sea (modified from Wikimedia Commons)

What’s happened so far?

While sequestration research is promising, political developments have been lagging. The most recent progress was that of the shortlisting of the DECC CCS competition to 2 projects. The Shell–Peterhead gas power station project based on North Sea storage and the White Rose project in Yorkshire, involving a coal-fired power station with subsequent storage in the North Sea. This decision, made last month, has been part of a slow, convoluted process in CCS funding. The competition first began in 2011 when, in the absence of other bidders, the Longannet CCS proposal was chosen for the first CCS commercialisation project. This was subsequently scrapped in late 2011 and a call for new proposals was not announced until May 2012, the shortlisting of which was finally announced in March 2013.

In the EU, the NER300 funding programme aims to create a renewable energy and CCS demonstration project comprising the best possible projects involving all member states. The NER300 programme, so-called because it contains a provision to set aside 300 million allowances (rights to emit one tonne of carbon dioxide) , was split into the NER200 and NER100 allowances (for more on the background to NER300 see www.ner300.com). However, following the submission of 13 CCS proposals for consideration for NER200, there were no CCS projects awarded funding in the first round and instead funding was allocated to 23 renewable projects. The second round, NER100, was called on 3rd April 2013.

Many have championed Northern Europe’s unique opportunity to push CCS development due to its home grown experience and knowledge of the North Sea oil fields, which represent a very viable location for UK- and Norway-based carbon storage, and there has been significant criticism of what is deemed to be the UK government’s slow commitment to the CCS and low carbon projects

So what’s the big hold up?

The delay in CCS development in the UK and Europe – coupled with the often disappointing and slow progress of climate change mitigation, most recently evidenced by the faltering discussions in Doha – has increased media, public and political pressure on governments to push ahead with the 2030 climate change targets, of which the advancement of CCS is a significant part.

But the delay has come about because of myriad concerns and unforeseen timing issues. From a policy perspective there has been historic concern over both the cost and environmental integrity of the capture and storage process. There is some debate as to whether the price of energy with attached CCS could become economical within a reasonable timescale, particularly as the start-up projects require a lot of capital investment. However, the cost should fall as the technology matures and economies of scale facilitate growth in this sector. Many of the issues over environmental integrity are being addressed through ongoing research, but a funded commercial-scale CCS project is an important part of the commercialisation process.

There are also some concerns that the development of CCS will act as a green light to the so-called ‘shale gas bonanza’ and will result in fossil fuel exploitation with impunity. While CCS will ease the decision to build shale gas into the energy profile, there should be some caution as to its role in the energy mix. Without a balanced combination of energy sources in the future energy profile, carbon emission targets will become impossible to meet. Additionally, the recent trend in discussing energy and water security together – from both a research and a policy perspective – has highlighted the high water consumption of CCS, which increases by 30-100% when added to a coal-fired power plant.

Slow progress on CCS has often been down to political issues such as the election of the coalition government in the UK – the two main parties of which have a frequently clashing energy agenda – and the widespread affects of the financial crisis, which have undermined the move towards green energy in the UK and EU. DECC, which runs the CCS competition in the UK, is headed up by minsters of opposing political parties with very differing views on this issue. This political tension, together with the long term instability of ministers in the department, has led to hampered progress in energy and environment policy.

A further issue, often omitted from the debate, is the potential for an independent Scotland – which is now a very real possibility following the announcement of the Scottish independence referendum in September 2014. This raises several issues with regard to the sovereignty of the North Sea and the potential storage locations contained therein.

The expeditious development of CCS is of significant importance if climate change targets are to be met with the continued use of fossil fuels. Both the science community and policymakers will be required to act together to improve the sustainability of CCS technologies but to also push the agenda in-line with climate change targets.

Flo Bullough

Policy Assistant at The Geological Society