The UK House of Commons Science and Technology Select Committee has recently launched an inquiry entitled “Climate Change: public understanding and its policy implications”, which is due to address the issue of communicating climate change research. This inquiry was raised following a recent surge in climate change scepticism and a diminishing public concern regarding its effects, with a survey suggesting that 76% of people were concerned by climate change in 2009 against 81% in 2008.

Climate change is certainly a topical issue. It lies at the junction between a panel of physical scientific disciplines (atmospheric physics, oceanography, ecology, chemistry and computing) and social sciences, being a prominent topic in politics and policy-making. There seems to be a constant flow of climate-related articles in the media. They may describe the negative effects of climate change on our environment or the place of climate and environmental change within education, with recent talks to include climate change on the school curriculum in the US being but one recent example. But to what extent do people really take notice? What does the public actually think of climate change and do they really consider our environment to be at risk? As a climate scientist, this got me thinking: How can we better communicate scientific results and the overwhelming consensus within the research community that action needs to be taken?

The inquiry: What, who and how?

In their call for evidence, the Commons Select Committee has outlined a series of questions to be discussed at the inquiry:

- What is the state of public understanding and opinion on climate change issues? What is the role of publicly funded scientists, Government Departments, scientific advisers and the media in communicating climate change?

- Who does the public trust?

- How can public understanding be improved? How important is this understanding in developing appropriate policy?

So what does the public think about climate change?

In September 2012, scientists from the British Antarctic Survey, the Universities of Cambridge and Cardiff and the Global Sustainable Institute at Anglia Ruskin University published a report on public attitudes to climate science and how this science is represented in the media. The purpose of the report was to examine how climate change research is being communicated, the public’s attitude towards it and the means by which this communication could be improved. To go about answering these questions, the investigators carried out a series of focus groups across the UK population. In each case, participants were presented with a range of UK newspaper, radio and television articles on climate science and invited to pick one article for discussion. They were then asked to judge the chosen piece based on the level of interest in the subject, how easy it was to understand and where the news piece could be improved.

Tongue of a glacier on Baffin Island, Canada. Credit: Angsar Walk.

The study revealed that 80% of the survey participants did believe that the world’s climate is changing through a combination of both human activity and natural variability. However, many people felt that they were not properly informed about new findings in climate science and therefore felt relatively uninterested in the field. More importantly, nearly half of the surveyed people believed that scientists exaggerate the seriousness of climate change and trust in “authority groups” such as government, industry, environmental groups, scientists and the media has decreased in recent years.

Climate change and public opinion – who matters?

Despite this growing skepticism, a recent poll published by climate and environmental policy news fact-checker Carbon Brief revealed that the UK population trusts scientists more than any other source to inform them about climate change. In second position, the poll placed Green charities, closely followed by BBC journalists. Far behind and in last place came both politicians and social media, with only 7% of voters trusting these sources to provide accurate, up-to-date information. In addition, the poll showed that as many as 64% of participants did not trust politicians’ information and 53% would not trust the information they read in social media.

Despite trusting scientists most, the number of concerned citizens is still dwindling. So how can we as scientists better convey our results and our concern? The last issue of the journal Nature Climate Change dedicated an editorial to the “climate consensus” and the factors affecting public opinion. The article revealed that the public would be more likely to believe that human causes are affecting long-term climate change if there was a clear scientific consensus that anthropogenic global warming is indeed happening. Luckily, this consensus does exist among the vast majority of climate scientists, so where is this information lost in translation?

Could, may, possibly, maybe… The uncertainty paradox

While the vast majority of people trust scientists, the 2012 report’s working groups also revealed that uncertainty is a big issue for public trust, with readers getting frustrated at fuzzy and seemingly contradictory statements. What is the point of saying that something could possibly happen without developing on this statement? On what basis should people then make decisions? The difficulty is of course that natural variability of the climate system and the complexity of the physical mechanisms involved mean that climate predictions intrinsically have a degree of uncertainty associated with them. There is no real debate among the climate scientific community that we humans are influencing our climate and that this will have consequences on a number of different parameters and sub-systems.

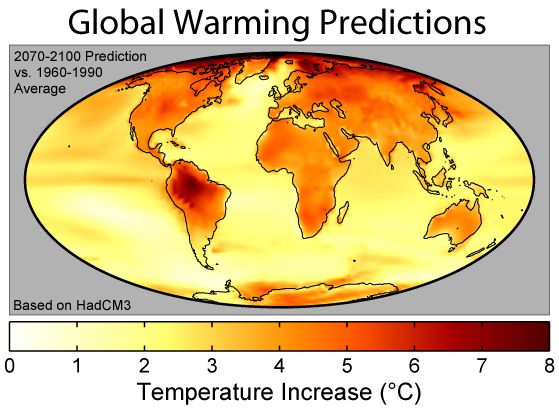

Global warming predictions for the end of the 21st century from the Hadley Centre HadCM3 climate model. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The question is what impact do these changes have in different parts of the world and to what degree can climate models assign a particular outcome to a specific human source? It is perhaps the definition of this uncertainty that scientists need to spend time explaining. Yes, a cluster of climate models may produce a range of results for a particular experiment. But ultimately they may all show the same trend or allow us to draw hard conclusions that can be translated to the public. When talking about climate forecasting at a recent Royal Meteorological Society meeting, Swedish Meteorologist Anders Persson stated that uncertainty is inevitable but must be acknowledged. He suggested that we stop blaming the models and start taking responsibility for uncertain forecasts. Uncertainty exists, full stop. Let’s start acknowledging it and, more importantly, explaining it.

So how can we scientists improve the communication of climate change research?

Given that scientists are in fact trusted and have a good understanding of the state of the art of climate research and the areas that still need exploring, it seems to me it is up to us to reach out to the public and talk about our research and its results. If, for each paper published in top scientific journals, the authors associated a short, simple piece of outreach to explain the steps taken to come to their conclusion and explain why they trust their results, perhaps more people would find an interest in climate research and would be willing to take personal action. But without this incentive and hard evidence clearly agreed upon by scientists, it is perhaps understandable that climate change is not the priority on everybody’s personal agenda. To put it in the words of financier Jeremy Grantham: “Be persuasive. Be brave. Be arrested (if necessary)”. In other words, let’s take risks and show our involvement and concern to make sure that it is heard by the public and policy-makers. This is possibly more easily achieved by established professors (and financiers such as Jeremy Grantham himself) than by young scientists trying to fight their way through to the next fellowship and piece of funding. But I believe the bottom line is true. Scientists must make a stand and show their agreement. Most of us are concerned and have the data to back this up, so let’s make it clear and give people a way to understand our work and ask their questions.

By Marion Ferrat, postdoctoral researcher at Imperial College London

matteo

I work in a museum. I coordinate a project for schools on the climate topic. I think this article should be handed-out much more. Gives a clear, honest idea of what has been done (in research and communication) by scientists and what should be done more. It might be helpful for science teachers too. To really understand the point of communicating climate change correctly.

Sara Mynott

Thanks for your kind feedback Matteo! You are welcome to copy, distribute and adapt the work in your school, provided the original author (Marion Ferrat) and source (geolog.egu.eu) are credited. Please take a look at this page to see how the content is licensed: https://blogs.egu.eu/geolog/copyright/. Feel free to share it with any teachers you think would be interested.