Buried beneath the soils of Burma lies a mystery that has been almost 70 years in the making: were a shipment of Spitfire aircraft concealed beneath a British airbase at the end of the Second World War? Dr Adam Booth, a geophysicist at Imperial College London and regular GeoLog contributor, is part of an archaeological team who are trying to unearth the truth in this tale. He’ll be posting to GeoLog from the field. This is Part 2 of the series; read his other posts here.

5 January 2013

All is set for the journey to Burma, and the geophysical crew leaves tomorrow. My flat in London currently looks like a geophysical store room, with four sets of equipment squeezed into it – along with Dr Roger Clark and Leeds PhD student Andy Merritt! We’re pretty excited to be moving one step closer to discovering the truth behind the buried Spitfires story. It’s a 16-hour journey from Heathrow to Yangon’s Mingaladon Airport – hardly an inconvenience for such a great survey opportunity!

From Britain to Burma…! Burma is highlighted in red, and the white star shows the location of Yangon. (Credit: Google Maps)

I thought I’d introduce the geophysics we’ve done to date, and explain why it supports the story of a burial taking place at Mingaladon Airport. I’m an ‘exploration geophysicist’, meaning that I use geophysical principles to locate and characterise some subsurface target (a well-known application is using seismic methods to detect hydrocarbon reserves). In archaeology, geophysics represents a cost-effective means of assessing the archaeological content of a given site prior to digging, and thereafter allows expensive excavations to be targeted at priority locations.

For the survey at Mingaladon Airport, the target is, obviously, a buried Spitfire plane (although, more correctly, there are understood to be a few-dozen of them!). The story goes that each Spitfire is ‘deconstructed’ inside a wooden delivery crate, which itself is the size of a modern shipping container. The image below shows a crated Spitfire being unpacked: the photo is taken in Malta, but crates similar to this are what is thought to be present at Mingaladon. Eye-witnesses report that the crates were hauled side-by-side into a channel that crossed the base, and then covered over. The suggestion is that the bases of the crates may be up to 10m beneath the modern ground surface!

British airmen unpacking a Spitfire from a delivery crate, in Malta, in 1942. (Photograph used here under the terms of the Imperial War Museum Non Commercial Licence.)

To a conflict historian, a buried Spitfire may represent a rich source of archaeological evidence, while a veteran may see it as a blast from the past; the exploration geophysicist sees it as something rather more mundane – a heap of metallic components buried at some depth in the ground! However, locating a target is all about exploiting contrasts in the properties of that target, compared to the soil in which it is hosted. Most of the metal in a Spitfire is aluminium, although its engine and cannons are made of steel. A good way to locate a buried Spitfire could be to consider the electrical conductivity of the subsurface. Soils are typically electrically resistive, whereas metals are obviously conductive: areas of elevated conductivity could correspond to the burial site. As steel is magnetic, the Spitfires could also be detected with magnetometry: buried steel will disturb the Earth’s natural magnetic field, so potential burials could be located from a map of magnetic field strength. The most comprehensive interpretations of the subsurface are obtained where recordings from different survey techniques are combined. As such, my 2004 survey comprised data acquisitions to measure both electrical conductivity and magnetic properties.

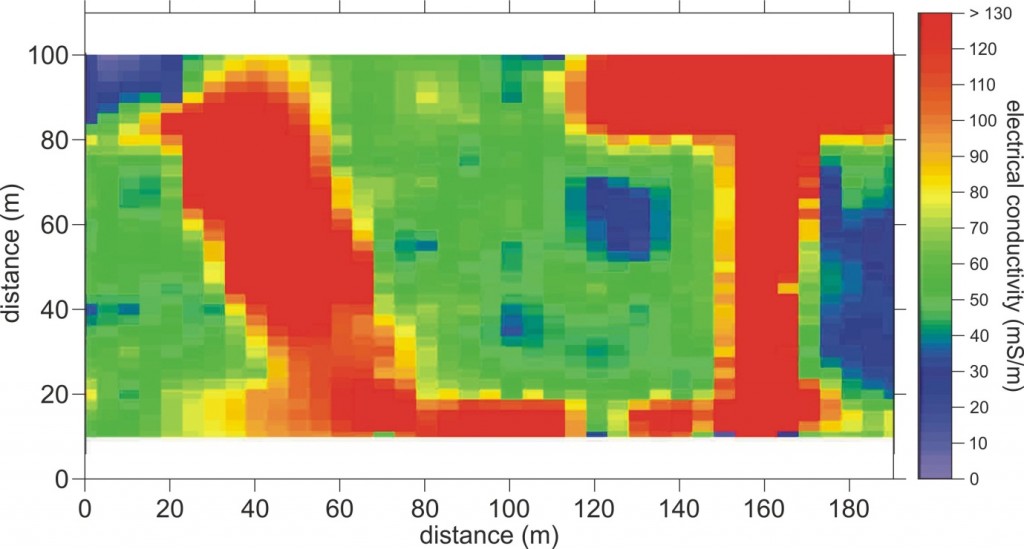

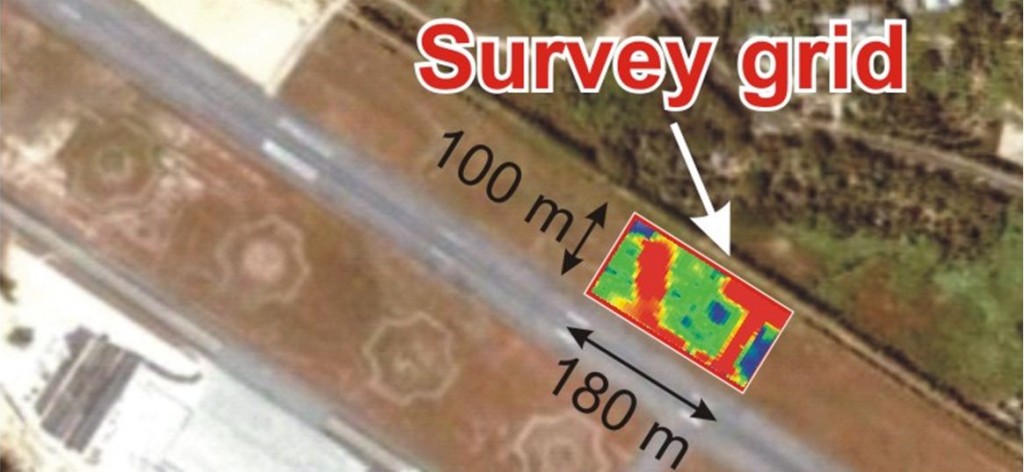

The image below is a subset of the electromagnetic (EM) dataset, acquired using Geonics EM34-3 equipment, which provides a measure of electrical conductivity. You’re looking at data in map-view: the survey grid is 180x100m in area, and the colours correspond to electrical conductivity – the highest conductivities are coloured in red. For reference, Mingaladon Airport’s runway heads along the bottom edge of the grid (see the lower map). Very obviously, there are two anomalous, high conductivity, areas at the site. It should be noted that the EM34 would lack the resolution to image individual components of a Spitfire, at least at 10m depth, and it instead shows the bulk conductivity trend. What strikes me about these anomalies, however, is their ‘straightness’. I employ two rules of thumb when interpreting data: nature doesn’t do right angles, and nor does it make straight lines. As such, these areas are immediately ‘suspicious’ of some sort of human activity.

However, it would be inappropriate to interpret ‘Spitfires!’ from these data. While the electrical conductivities are sufficiently high to be indicative of metal, a war leaves behind a great deal of metallic debris and we could simply be looking at a bulldozed dump-site. However, what is compelling about these data is that the location of the left-hand anomaly exactly matches the burial site identified by certain eye-witness veterans. A trial excavation in 2004, over this anomaly, revealed wooden planking at a depth of around 5m – an isolated plank, or the top of a delivery crate…? Unfortunately, our group’s arrangement with the government did not extend far enough to check. So near but so far, the hole was backfilled – Mingaladon would hold onto its secrets for another few years…

…Until now! Starting in a few days at Mingaladon, the first task of the geophysics crew will be to confirm and update the previous EM survey. Thereafter, our archaeologists need an estimate of target depth in order to design the excavation. The depth of an anomaly cannot be constrained reliably from EM data, and electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) is better-suited to this task. Andy Merritt uses ERT in his PhD research, and he’ll be acquiring ERT lines through the centre of the EM anomalies. The expectation is that we’ll be able to make a nearest-metre estimate of the target depth.

The next update will be posted from Burma itself, when I’ll hopefully have some hot-off-the-press geophysical images for you, and some information from the archaeologists about how they’re planning to excavate and recover whatever we find. Stay tuned to GeoLog!

By Adam Booth, Imperial College London

Jen Webster

My late father was RAF air crew stationed outside Rangoon involved in dismantling and crating up spitfires so it is a true story. He used to say that the Japanese were too close for them to risk burial in Burma so they were shipped into India.

Stephan Wilkinson

Are you going to Burma or not, since they’re apparently already digging? Which is another way of asking, do I leave this website bookmarked or delete it?

ferreira

Hi Stephan, I am waiting for Burma updates from Adam, but I’m unsure what his current internet connection is like. I will publish his new blog post as soon as I receive it.